I have always loved ceramic vessels, whether they be bowls, pitchers, or even plates. They are for me a kind of small architecture in the way that they define and contain space. I particularly love when they are hand crafted. Clay, earthen ware, in particular shows the hand of the maker in beautiful ways.

Perhaps this love of things ceramic is why I have long had a fascination with Testaccio—the Roman neighborhood, a twenty minute walk down the hill and across the river south of the Janiculum from where we are. The center of the neighborhood and its namesake is Mount Testaccio. The Mountain is an artificial one—created by the systematic piling up of the shards (Testae in Latin) of discarded amphorae that were primarily used to import olive oil into Rome.

“It is one of the largest spoils heaps found anywhere in the ancient world, covering an area of 2 hectares (4.9 acres) at its base and with a volume of approximately 580,000 cubic meters (760,000 cubic yards) containing the remains of an estimated 53 million amphorae. It has a circumference of nearly a kilometer (0.6 miles) and stands 35 meters (115 feet) high, though it was probably considerably higher in ancient times. It stands a short distance away from the east bank of the Tiber River near the Horrea Galibae where the state-controlled reserve of olive oil was stored in the late 2nd century AD.” (Wikipedia - Claridge, Amanda (1998) “Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide”)

It is now the center of a neighborhood of the same name. The neighborhood was historically working class and defined by the industries that were located there. This included the massive 19th century slaughterhouses. It is not surprising to learn that Rome’s soccer club, AS Roma, first played in a stadium in Testaccio and that the neighborhood is home to a long culinary tradition rooted in offal, the often discarded parts of animals from hooves to tripe.

It is these restaurants, particularly Checchino Dal 1887 that first got Marian and me to Testacchio on our honeymoon twenty five years ago. The restaurant is built into the hillside of the “mountain” and started as a wine store. Reputedly the wine caves that are dug into this side have a natural cooling property due to the way that air can move through the compacted shards; they still have the wine cave. The family, descended from great grandmother Ferminia, continues to run the restaurant. We particularly love their version of pasta all’amatriciana and the scottadito—lamb chops that are finely cut and “burn your fingers” when you pick them up.

In our first week here Marian wanted to go down and explore the new market that stands across the street from Checchino and adjacent to the long abandoned slaughter houses. The new market is wonderful (more about this later). Afterwards, we decided that we should walk around the hill as we never had—it is amazing that above the houses that ring it you can see the shards that make it up.

So, this sets the stage for Marian and my visit this past Saturday, October 7th, to Trajan’s Market. After spending time thinking about the Macellum in Pozzouli, I wanted to come back to this grand set of spaces of Imperial Rome. It has now been turned into the Museum of the Imperial Fora which you can see outside of its windows. Here one finds fragments of the architectural and sculptural decoration of these vast complexes. The scale of these elements—they are huge—really make you appreciate how large these complexes were.

I will do a later post on the market buildings—as I need to do some more reading on them—the extent to which they were a market seems to currently be debated.

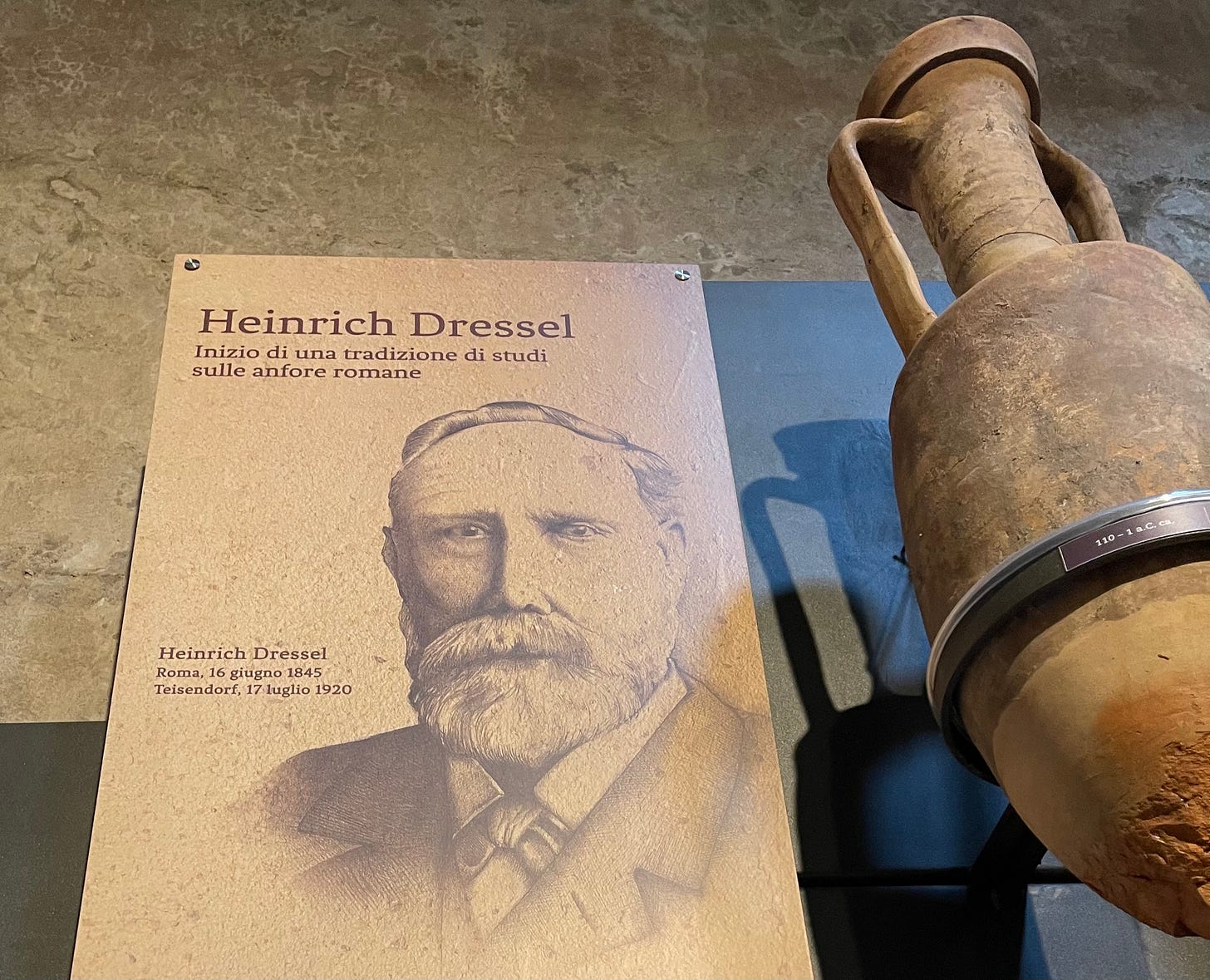

Tucked into a space that was a medieval addition to the complex (a well and a cistern to be precise) is a wonderful exhibition of Roman amphora. It was the archaeologist, Heinrich Dressel, who first studied these two-handled containers designed to both store and transport wine, olive oil, garum (fish sauce) and the like throughout the empire. This small exhibition has captivated me. I love the variety of shapes that amphorae come in. They are both workaday and elegant. They have also spurred me to think about the food system in the ancient Roman world. How you feed a city of over a million inhabitants has always been a daunting proposition. Dresser’s study and categorization of amphorae has helped to unlock an entire field of study which has allowed the tracing of how food shipments worked throughout the ancient world.

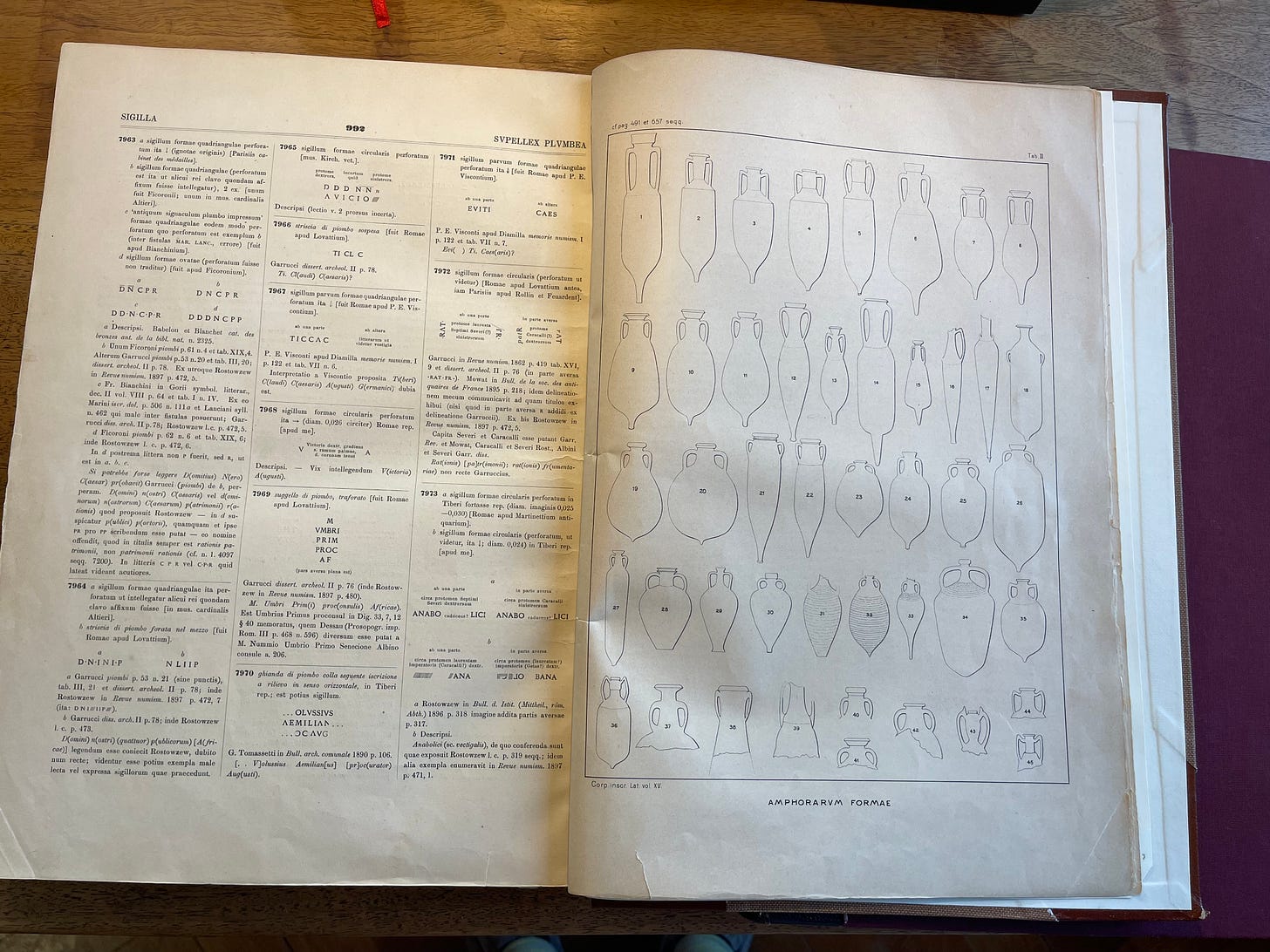

The beauty of being at the Academy is that after one is inspired in the field or in this case at a museum—one has the resources to go down the rabbit hole. I was particularly struck by the “Tavola Dressel” and wanted to learn more about this German Archaeologist.

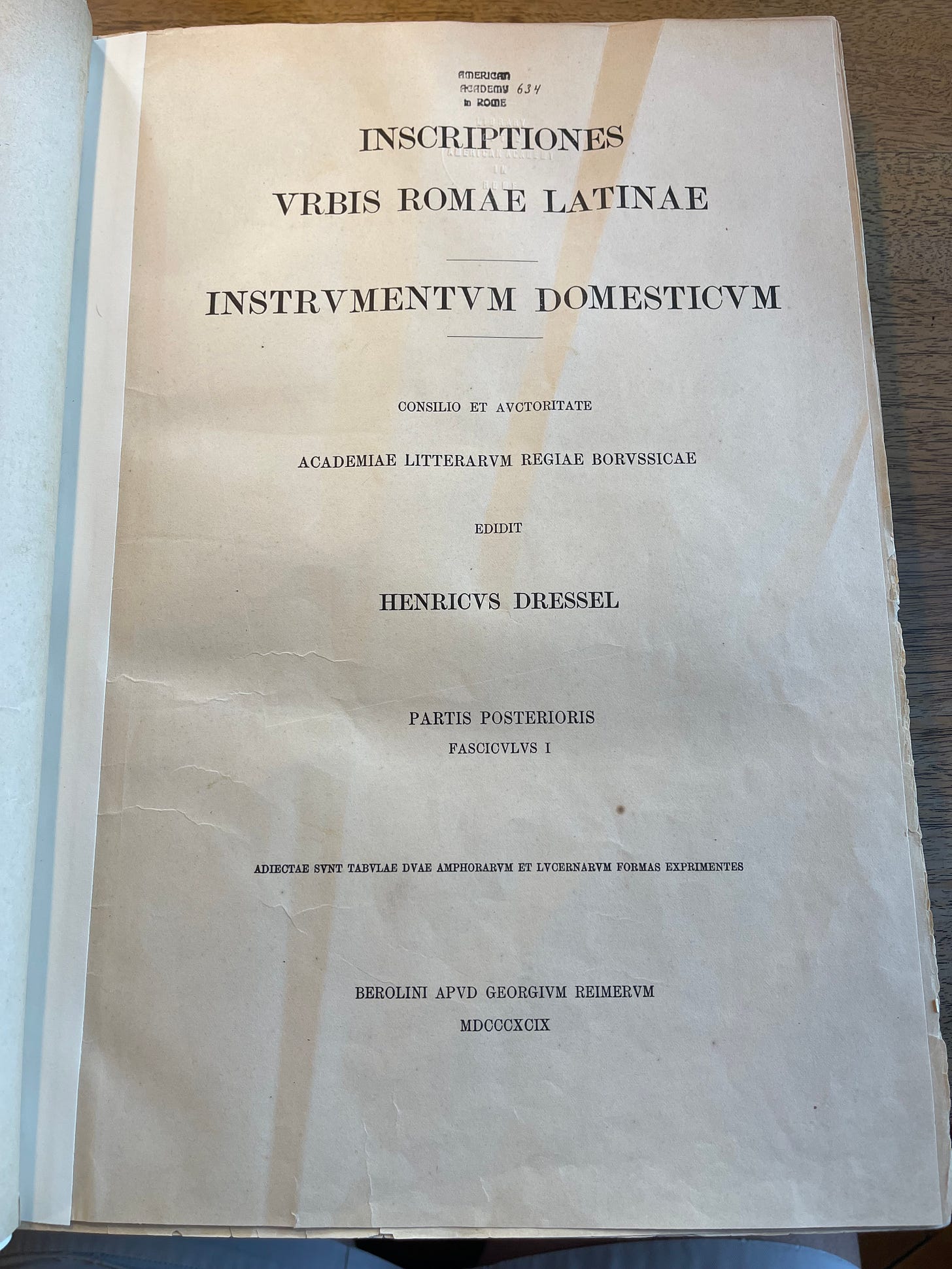

In the main reading room of the library I found the many, many volumes of The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum of which Dressel’s two book set published in 1899 is but one of the volumes. In it he catalogues and describes 7,973 amphorae. This includes descriptions of the makers stamps and the all important Tituli Picti which are hand written notes on the amphorae that recorded their provenance, journey, and dating. The majority of the Amphorae from Testaccio are of the type that Dressel categorized as Dressel 20. They are globular in size.

Dressel had begun his research on Testaccio in 1873, but in 1878 a huge cache of Amphorae of various types were found in 1878 during the construction of the urban district of Castro Pretorio, for the new capital of Italy. There was a significant cache of amphoras that, around the middle of the first century CE, were arranged in layers to fill a section of the moat of the old republican wall (Servian Wall) that is no longer in use. Until that time, scholars were interested only in the texts that could be inscribed on the amphoras, and not on the object itself.

I have not been able to find much biographic information on Dressel other than that he was born in Rome in 1845 and died in 1920 in Teisendorf. He studied under Theodor Mommsen in Berlin and received his doctorate from the University of Göttingen. In 1878 he became a professor at the German Archaeological Institute in Rome and in 1898 was appointed director of The Numismatic Collection in Berlin. Beyond this and a list of books there is little on the life of this man, who is mentioned by Peacock and Williams in their book, Amphorae and the Roman Economy, as almost losing his eyesight transcribing the thousands of markings that allowed him to systematize these amphorae. His aim was not to create a general classification, but to provide a graphic documentation closely aligned to the epigraphic collection.

Dressel built a bridge between archaeology and epigraphy. Starting from his work scholars understood the role of studies on amphoras in the reconstruction of ancient trade and production and developed a fruitful research tradition.

The Academy Courtyard, cortile in Italian, is the heart of Charles McKim’s design and reprises the central outdoor space of the classic Italian Palazzo or Villa. From the beginning, it also was an outdoor museum of antiquities. In this way it was styling itself after the great Roman palaces including what was to become the Vatican Museum. The challenge with these past collections is that they were installed with an eye for aesthetic effect—not really as a way to study the architectural fragments.

In 2015 The Academy published The Collection of Antiquities of the American Academy in Rome. The principal portion of this collection is housed below our apartment in 5B. It is where I found the plate decorated with fish in my post on the Mare of Naples.

Archer Martin in his discussion on the Roman amphorae in the collection sums up the Academy’s collection:

The AAR’s amphora collection was never intended to illustrate the history, typology, or geographic origins of ancient amphorae. It consists of three unequal parts that arose for different reasons and have different characteristics. One group includes 216 fragments of Dressel 20 amphorae of epigraphic interest, mostly stamped handles. The the second is a group of miscellaneous pieces, mostly epigraphic, acquired by the Academy at various times and in differing ways. The third is made up of a half dozen amphorae of various types, which were mostly placed around the Academy courtyard as decorative antiques.

Martin continues in describing Epigraphic collection of Dressel 20 Amphorae handles:

This group consists almost exclusively of pieces from Testaccio, the artificial hill in the southern part of Rome not far from the Tiber made up overwhelmingly of Dressel 20 amphorae. They were involved in the massive movement of olive oil from Hispanic Baetica (southern Spain) to the capital that was promoted by the “annona,” a sort of state welfare system, between the first and third centuries. Upon their arrival the amphorae were emptied of their contents and discarded in an organized way, resulting in the formation of the artificial hill, named the “Pottery Hill,” from the Latin “testa,” “pot,” or “piece of broken pottery.”

Martin is very dismissive of the amphorae used as decoration:

[They] must have been bought on the antiquities market, although no record concerning them has been found. They are of some interest in documenting the taste and restoration methods of the time. Several of these amphorae are intact or nearly complete and required no mending. Two others are recomposed from pieces that belong together, one using metal clamps and cement and the other with cement. A third piece, lacking a handle and part of the rim, has an integration in cement. Finally, one piece was a pastiche made up of a body, a spike of a different vessel of a similar type, and a rim that is not pertinent, even topologically, to the rest—all held together with great quantities of cement and wire. . .

Among these decorative pieces, the Dressel 20 amphora (inv. No 9477) is especially interesting for us because, although it does not itself present a potter’s stamp on the handles, it represents the type to which so many handles and other fragments from Testaccio belong. It is reconstructed from three pieces: the main piece, consisting of a part of the rim and most of the body; a rim fragment glued to the first; and a base fragment with some of the lower body, which is fixed to the main piece with lead clamps. This type of globular amphora served, as we have seen, for the transport of olive oil from the valley of the Guadalquivir and its tributaries in the province of Baetica. It was produced from the reign of Tiberius until the third or fourth Century. Specific examples can be dated more closely on the basis of the shape of the rim—in the case of the Academy’s amphora, to the middle of the first century.

The epigraphy of Dressel 20 amphorae is very complex, with stamps placed on the handles before firing, and therefore concerning the vessel itself, as well as the control marks pertaining to the contents, adding at various points in the course of their travel from Spain to Rome.

The courtyard installations of archaeological fragments, like those in the Vatican and other great Roman palaces, are now their own pieces of history. I will say that they do make the material an immediate part of your daily life. You see the ancient inscriptions on the wall and then you get a Latinist sitting next to you at lunch or dinner and it starts a conversation with them translating what is said on each fragment. The presence of the amphorae has probably been provoking me without knowing it—just waiting to be nudged by the exhibition at the Markets of Trajan.

Paul Rudolph who designed the dramatic Brutalist Art and Architecture Building at Yale in 1963 took many of the Beaux Arts casts of ancient architectural fragments and sculpture and placed them around the building. A great statue of Minerva dominated the first floor atrium until it was discovered that the body was in fact a true ancient Roman sculpture. I would argue that while these fragments are “decorative” they serve a pedagogical purpose—they provoke in subconscious ways and force us to ask ourselves about our relationship to history.

Archer Martin refers several times to Peacock and Williams’ Amphorae and the Roman Economy: An Introductory Guide. This “guide” picks up the story of Amphorae Studies post Dressel. They note that in the 1970’s Amphora Studies became accepted. Crucial for them is that the analysis of shape is now being augmented by an analysis of fabric in the types of clay and residue present in the Amphorae.

As in much that I am encountering in my time here in Rome, there is the ever present challenge of first principles or definitions:

One of the most vexed issues in amphora work is the question of classification and today the specialist is confronted with a bewildering choice of ways to describe a vessel. There is no general agreement on how to classify containers and indeed there is no widely accepted definition of what an amphora is. However, Virginia Grace (1961) has mentioned some of the more important criteria, which form the basis of a definition.

There is a variety of shapes, but they have in common a mouth narrow enough to be corked, two opposite vertical handles and at the bottom usually a tip or knob which serves as a third handle, below the weight, needed when one inverts a heavy vessel to pour from it. Afloat base big enough for the jar to stand on would give no purchase for lifting. Attached bases like those on small two-handled vases for the table would add uselessly to the weight of these containers and to the inconvenience of stowing them as cargo as well as the cost of manufacture (p5).

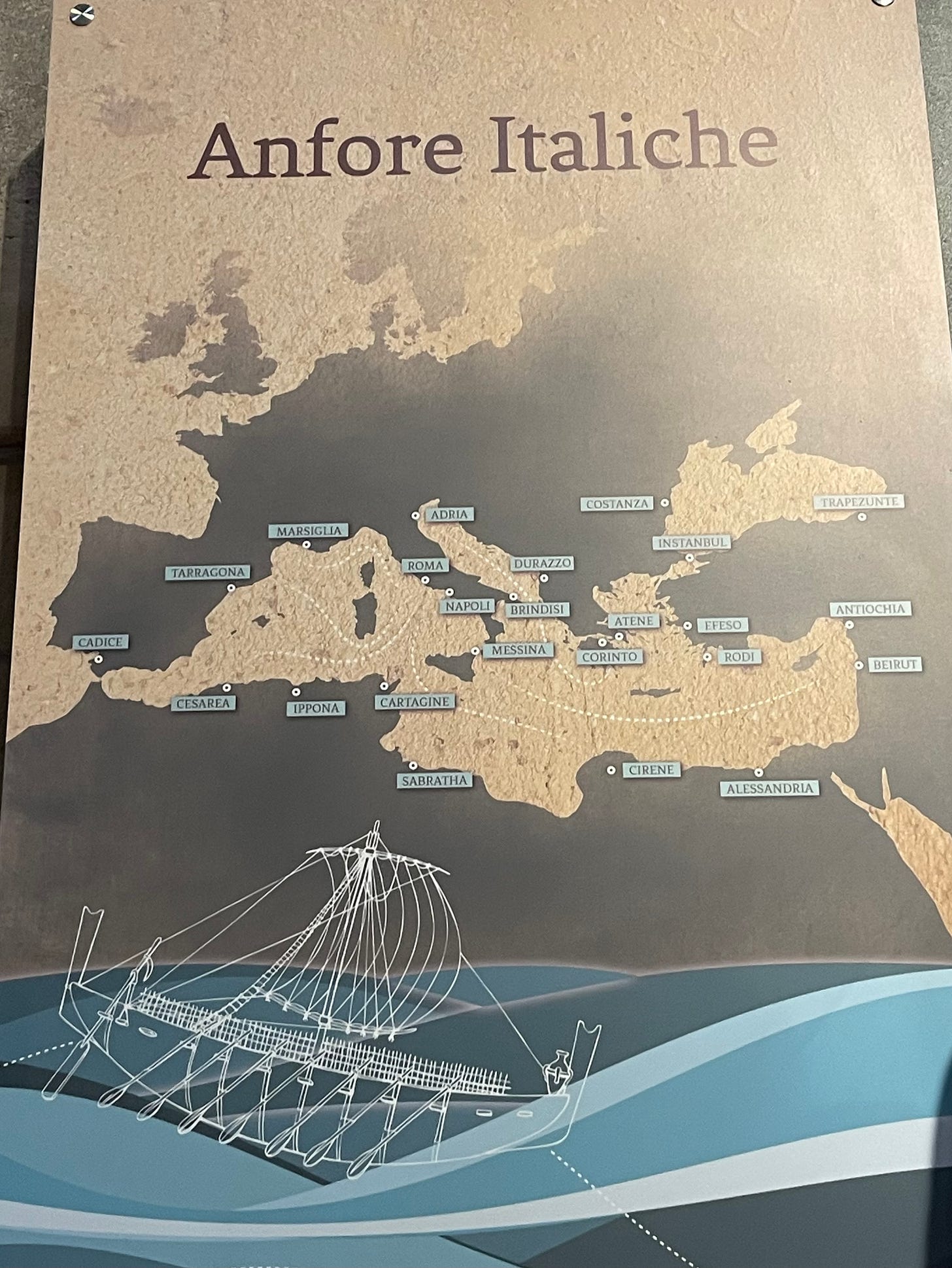

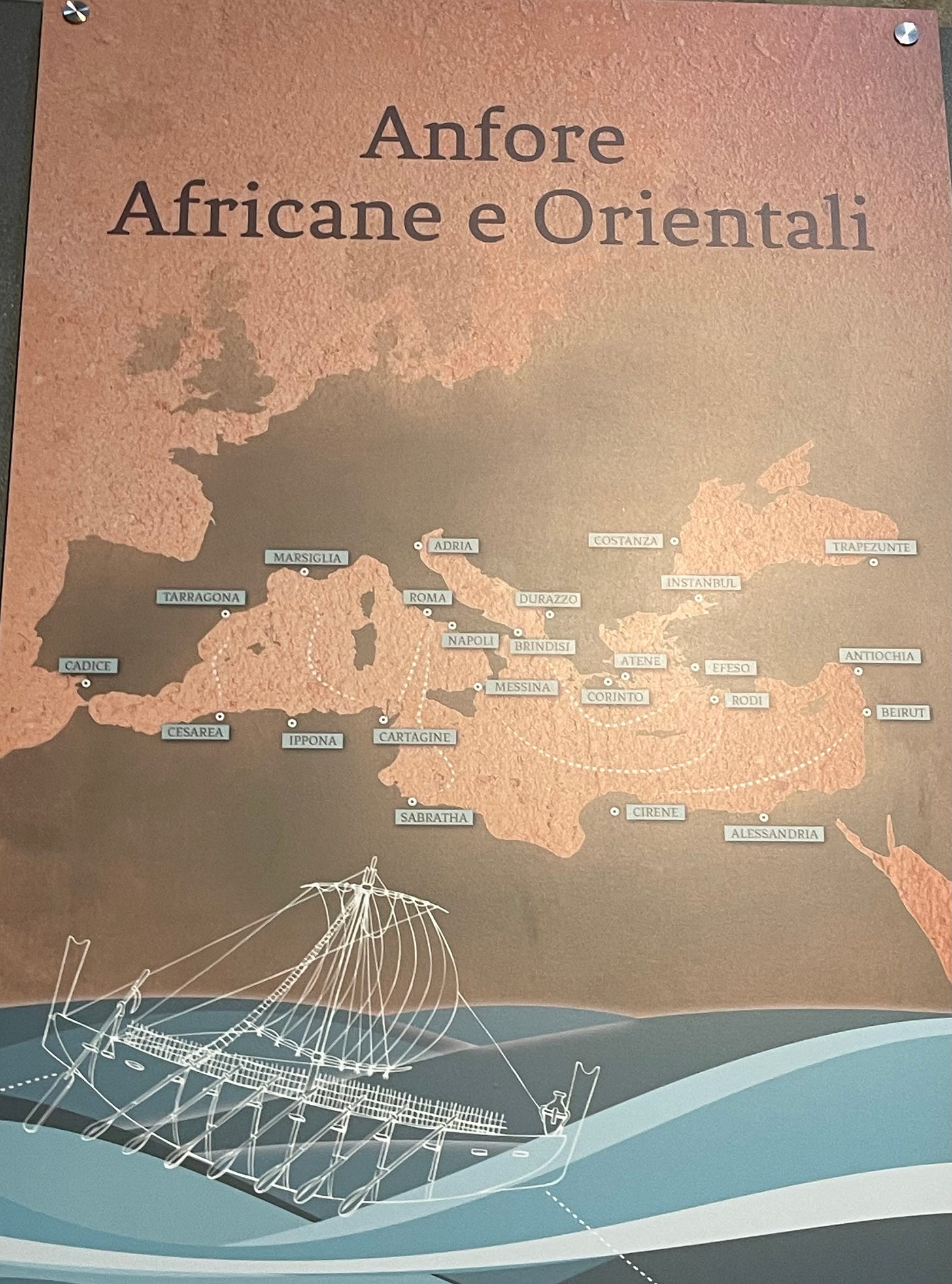

The discovery of shipwrecks with intact amphorae over the course of the twentieth century has been a major factor in the blossoming of amphorae studies. The presence of certain types of amphorae on certain ships in certain locations has led to a better understanding of trade routes throughout the Mediterranean. The exhibition at Trajan’s Market looks at how amphorae from Italy, North Africa, and Spain traveled around the Mediterranean. It is Dressel who, on the basis of his epigraphic analysis of the Type 20 Amphorae, led to the realization of the quantities of olive oil being imported into Rome.

The huge numbers of broken amphorae at Monte Testaccio illustrate the enormous demand for oil of Imperial Rome which was, at the time, the world’s largest city with a population of at least one million people. It has been estimated that the hill contains the remains of as many as 53 million olive oil amphorae, in which some 6 billion liters of oil were imported.

Studies of the hills composition suggest that Rome’s imports of olive oil reached a peak toward the end of the 2nd century AD when as many as 130,000 amphorae were being deposited on the site each year. The vast majority of these vessels had a capacity of some 70 liters. From this, it has been estimated that Rome was importing at least 7.5 million liters of olive oil annually. The vessels found at Monte Testaccio appear to represent mainly state-sponsored olive oil imports. It is very likely that additional quantities of olive oil were imported privately. Excavations carried out in 1991 show that the mound had been raised as a series of level terraces with retaining walls made of nearly intact amphorae filled with shards to anchor them in place. Empty amphorae were probably carried up the mound intact on the backs of ponies or mules and then broken up on the spot with the shards laid out in a stable pattern. Dates from 140 to 250 CE, but it’s possible that dumping could have begun on the site as early as the 1st century BCE. (Wikipedia - Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome:And the End of Civilization and Juliann Bennett, Trajan Optimus Princeps: A Life and Times)

Clearly, Ancient Rome had grown to a size where it was not possible to feed everyone based on a 100 mile foodshed. Rather the Mediterranean became the foodshed.

This brings us back to Testaccio and the power of these shards of clay to teach us. The new Testaccio marketplace designed by Marco Rietti was opened in 2014. The 5,000 square meter market hall is complemented by a mixed use building that has a drug store and super market. There is also a small hotel and office space. It is a beautiful complex that brings together the geometry of the single tenant (the geometry of the “box”) into a compelling whole. The boxes and the shaded passageways are of elegant white steel—but what links the building brilliantly to the neighborhood is the terra cotta screen. Terra Cotta, the humble material of amphorae and Roman brick, is the backbone of Roman architecture.

After showing me the drawers of Dressel 20 amphorae handles, Valentina Follo, the Curator of the Norton-Van Buren Architectural Study Collection, pointed out that the Romans followed the same practice of stamping their bricks.

I simply HAD TO read this post right away. Fabulous. I feel such a connection to Testaccio for many reasons. Thank you for this Hans. I learned so much. Isn't it different though, to read about a place (or to write about a place), and the many layers that collaboratively give meaning to that place, when one has physically experienced that place as a human being whose feet have felt that ground, whose nose has smelled the aromas, whose eyes have seen the horizon lines and whose ears have heard the sounds of living there and whose heart has conjured up it's own sentiments inspired by that place? It's just different. I'll stop. Thank you Hans. This was fun and life inspiring for me!! (This is Lib)

I had no idea about any of this. Thank you for all these posts.

Great photos of Marian!