The day before yesterday, I met with one of the librarians here at the Academy. I wanted to learn more about the building that we are living in which is glamorously known as 5B—the address to the main building being 5 Angelo Masina. He handed me a copy of The Janus View. This collection of essays is a dream come true for someone like me who always wants to know more about the history of where he is. The Janiculum is on the western side of the city and the Academy is at the highest point inside the walls. I mentioned in an earlier post that the Academy garden was the scene of fierce fighting in the summer of 1849 when the Roman Republic (that had been recently proclaimed) was besieged by the French who were working for the return of the Pope. This story is told in The Pope who would be King by David Kertzer. The story of this siege runs through many of the essays in The Janus view because not only do the pre-unification buildings figure into the action but also because the subsequent development of this area is a massive commemoration of this first effort to bring secular rule to Rome. Almost all of the street names commemorate individuals involved in this struggle (More on this in a future post).

Marian and I went down to San Pietro in Montorio to see Bramante’s Tempietto yesterday afternoon (24 on the map).

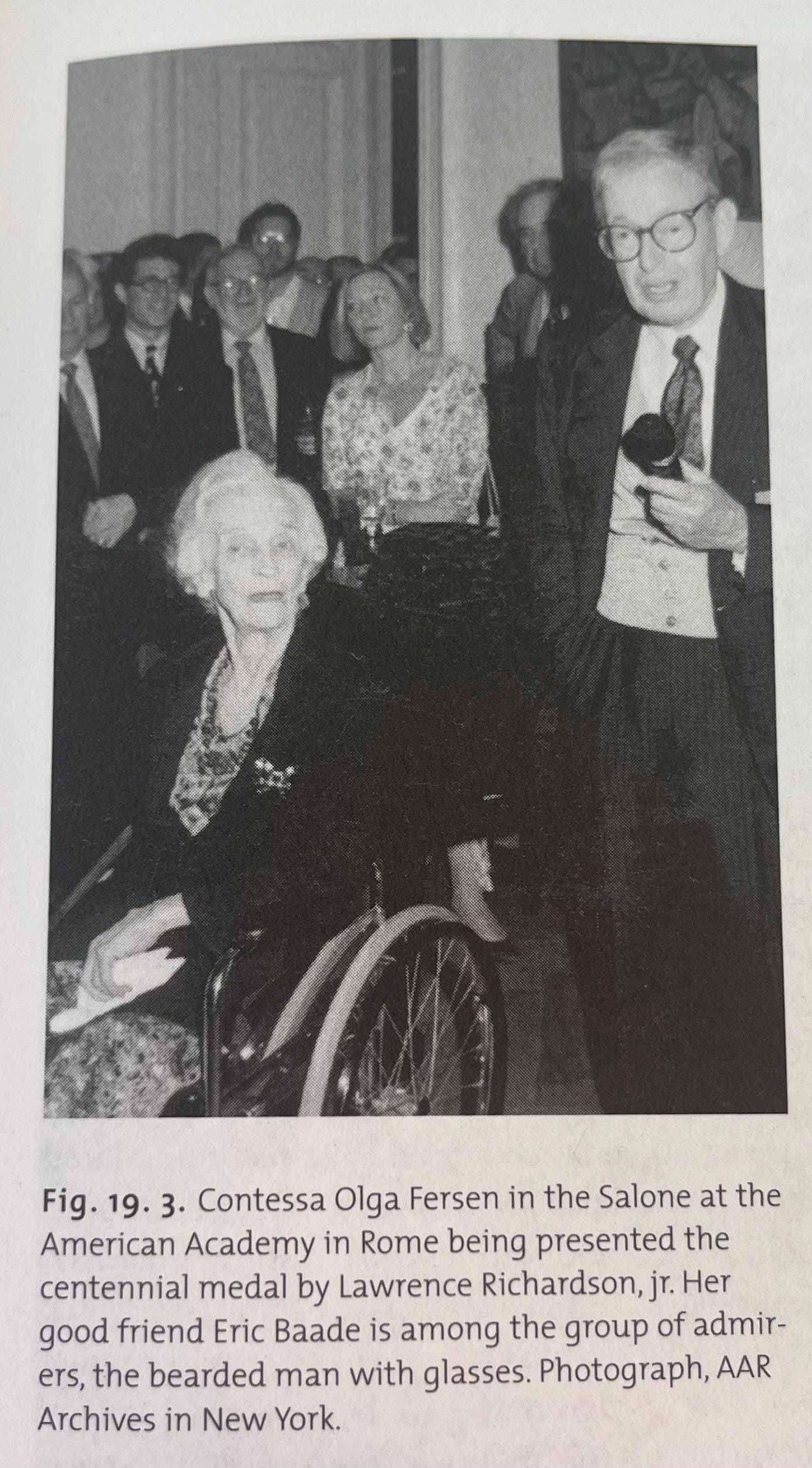

Unfortunately, it was closed so we went through the church and then read the essay in The Janus View. While leafing through the table of contents we stumbled on the title of Chapter 19, “The Villa Sforza Cesarini and the Pensione Fersen.” Opening the book to page 157, I saw Contessa Olga Fersen staring out at me. I had lived at the final iteration of the Pensione Fersen during that summer of 1983 when I worked in Rome after the semester studying at Syracuse University in Florence.

I had been put in touch with the Contessa by Eric Frank who had taught art and architectural history at Syracuse. He had been a Fellow at the Academy and was, at the time, continuing work on his dissertation on Antonio del Pollaiuolo, the Renaissance painter, sculptor, engraver and goldsmith. As I remember it, the Contessa was born in 1900 and had come from Russia at the time of the Revolution because their family was nobility and Rome was a place they knew. Her family had become connected with the Academy and they had let rooms in their home.

The Contessa was 83 when I was staying with her (my memory that she was born in 1900). She struggled mightily to get around, but always served me breakfast on a wheeled cart. The cart was assembled by a woman by the name of Carla who was somewhat crazy and they would yell at each other. Carla would dust the apartment with terry cloth rags that she would attach to her feet and slide around on. I remember being so impressed by the fact that the Contessa spoke Russian, French, English, Italian, and perhaps also Greek and Spanish. She was extraordinarily cultured and had met so many interesting people. One conversation that I remember vividly concerned the Trans Siberian Railroad. I had mentioned that I was interested in riding on it. She told me that she had wanted to as well and had been told that she had to wait until she was 18. Of course the Revolution came when she was 17; the moral from her was not to put off what you want to do.

Lawrence Richardson, Jr, a FAAR in 1950 wrote the chapter on the Pensione Fersen. He was also the Mellon Professor-in-Charge of Classical Studies. From that chapter I learned that my dating of the Contessa’s life was four years off (1904-1998). I am also happy to learn that she lived to see the fall of the Soviet Union.

As this essay fills in a lot of specific points I quote at some length:

At the time the Fersen were one of five émigré Russian families living in the Villa Sforza Cesarini. During the Russian revolution they had been staying at their summer house in south Russia on the Black Sea, when word came that they must leave at once to assure their safety. Like many other Russians in similar circumstances, they took ship, by way of Istanbul, made for the Mediterranean and asylum abroad, wherever they could find an enforced exile most agreeable. Some stayed in Istanbul; others went to Athens and Smyrna; and many emigrated to Rome, which they already knew and loved from trips abroad.

But Countess Fersen had to flee her home without her husband Count Fersen stood high in the Russian aristocracy, a personal friend of the Czar. Because he held a command in the White Army, he could not leave with his family. The Fersen had produced four children: Paul, Alexander, Elizabeth (known as Lili), and Olga, the youngest. The health of their young daughter Olga was poor, and there was concern about obtaining treatment for her, as well as finding an accommodating climate. But the Contessa was a resourceful woman, and the family was well connected, and through these connections found an apartment in the Villa Sforza Cesarini.

. . . with so many Russian families in residence in the Villa, it was rented out piecemeal, room by room. (Esther Van Deman’s) establishment there with the Fersen almost immediately drew other members of the Academy family to seek accommodations there, and in the period between the two World Wars the guest book came to include a roster of illustrious American scholars. . . There have been many stories told of life at the Pensione Fersen in the years between the two world wars, undoubtedly some of them embroidered. The most vivid in my memory is of the annual horse show in the Villa Borghese that took place in May. The whole Russian community of Rome would turn out for this event, dressed to the nines in pre-war finery, armed with parasols and picnic hampers . . .

I (Lawrence Richardson, jr) first savored the pleasures of the Pensione Fersen just after the second World War. By that time Miss Van Deman had died . . . The Villa had been repossessed by its owners. . . The dispossessed Fersen had then found lodgings in a comfortable villa of vaguely Tuscan character on Viale Aurelio Saffi, just outside the walls where they plunge down the hill to the Tiber.

I (Lawrence Richardson, jr) was young and new to Rome and was put under the tutelage of Madame Sonia de Daehn, the last living granddaughter of Czar Nicholas 1 . . . she was . . . The only one left, besides Olga Fersen . . . of the Russian colony that had once lived in the Villa Sforza Cesarini . . .

Later still, in the 1960’s, the Pensione Fersen had to move again, this time to a large airy flat in one of the new palazzi rising off the Piazza Cucchi, between the Viale dei Quattro Venti and Villa Doria Pamphilj. My wife and I were staying there one summer, by which time the only other permanent paying member of the ménage was the Countess Leonora Lichnowsky, a deep voiced German aristocrat who had somehow wound up a colorful career of global range employed at FAO. She tended to dominate the conversation at dinner, but with such a range of interests and of experiences that one was never bored. Eventually she even outlived Olga Fersen, who despite a brittle frame and frail health lived well into her nineties (1904-1998). Olga lived long enough to receive in 1994 the American Academy’s centennial medal, an honor she greatly prized.

I am grateful for Lawrence Richardson jr’s reminiscences because they have brought back the Contessa vividly to me as well as the Countess Lichnowsky. In my memory they were in fact cousins. Contessa Fersen pointed this out and said it was just like the Tsar and the Kaiser were cousins.

Having read all of this outside the door of the Villa Sforza Cesarini, I decided I needed to revisit my version of the Pensione Fersen at 3 Piazza Cucchi. I headed south from the Academy and exited the walls at Via Fratelli Bonnet. This is the street from which I would take the bus to and from work each day that summer. The tavola calda where I would often buy dinner is no longer there but the walk was so familiar.

3 Piazza Cucchi is actually a group of buildings and the Contessa had two apartments in the south-west. In this way she controlled an entire floor.

Next, I walked east through the Monte Verde neighborhood. It was here that I purchased Marian’s birthday cakes on our first day in Rome. I decided to go look for the vaguely Tuscan villa on the Viale Aurelio Saffi. I found one that is the logical candidate. The photo of which is above.

I have always looked back on the experience of living with the Contessa Fersen as a throwback experience to an earlier time and my life is richer for it. I am glad to now be able to better situate the experience in the topography of the Janiculum and in the topography of my mind.

Hans - wonderful descriptions that remind me of my favorite types of travel books - ones written in the early days of travel when each sight was a revelation.

And you make me think back on my trips to Italy - very pleasant reminiscences.

Best to you both!

Malcolm